[ad_1]

From the Winter 2024 problem of Residing Fowl journal. Subscribe now.

When hordes of chickadees, finches, and woodpeckers descend on a yard chook feeder, squabbles are sure to erupt: Typically getting a alternative morsel means muscling your approach into place.

Minimizing battle in these conditions is nice for birds, says Cornell Lab of Ornithology Analysis Affiliate Eliot Miller: “It takes vitality to battle, and it may be harmful, so it normally is smart to keep away from it.”

In 2017, a workforce led by Miller used Venture FeederWatch information to research such conflicts—moments when one chook displaces one other at a meals supply. The outcomes, printed within the journal Behavioral Ecology, gave rise to a dominance-hierarchy rating for yard birds: a information to which species had been more than likely to carry their floor in one-on-one confrontations with different species, and which of them had been extra prone to flip tail and fly.

Now, different scientists are selecting up the place Miller left off, utilizing an ever-growing set of FeederWatch information to dive deeper into the behaviors, social relationships, and bodily traits that form battle on the chook feeder.

Biologist Roslyn Dakin of Carleton College in Canada was impressed by Miller’s 2017 examine to look into whether or not a chook’s social tendencies have an effect on their place within the pecking order. For instance, some birds, similar to finches and Home Sparrows, are social butterflies that usually go to feeders in teams, whereas others, similar to woodpeckers and nuthatches, usually tend to be lone wolves.

Working with Carleton PhD pupil Ilias Berberi, Dakin analyzed 6.1 million FeederWatch observations to find out the typical group dimension at feeders for 68 species.

“What we realized as soon as we obtained into [the FeederWatch data] is that it really presents all types of alternatives that we don’t have in any other case,” says Dakin. “It lets us ask questions that we couldn’t probably ask by the observations of anybody scientist or perhaps a small workforce of scientists as a result of nobody individual might observe communities throughout a whole continent.”

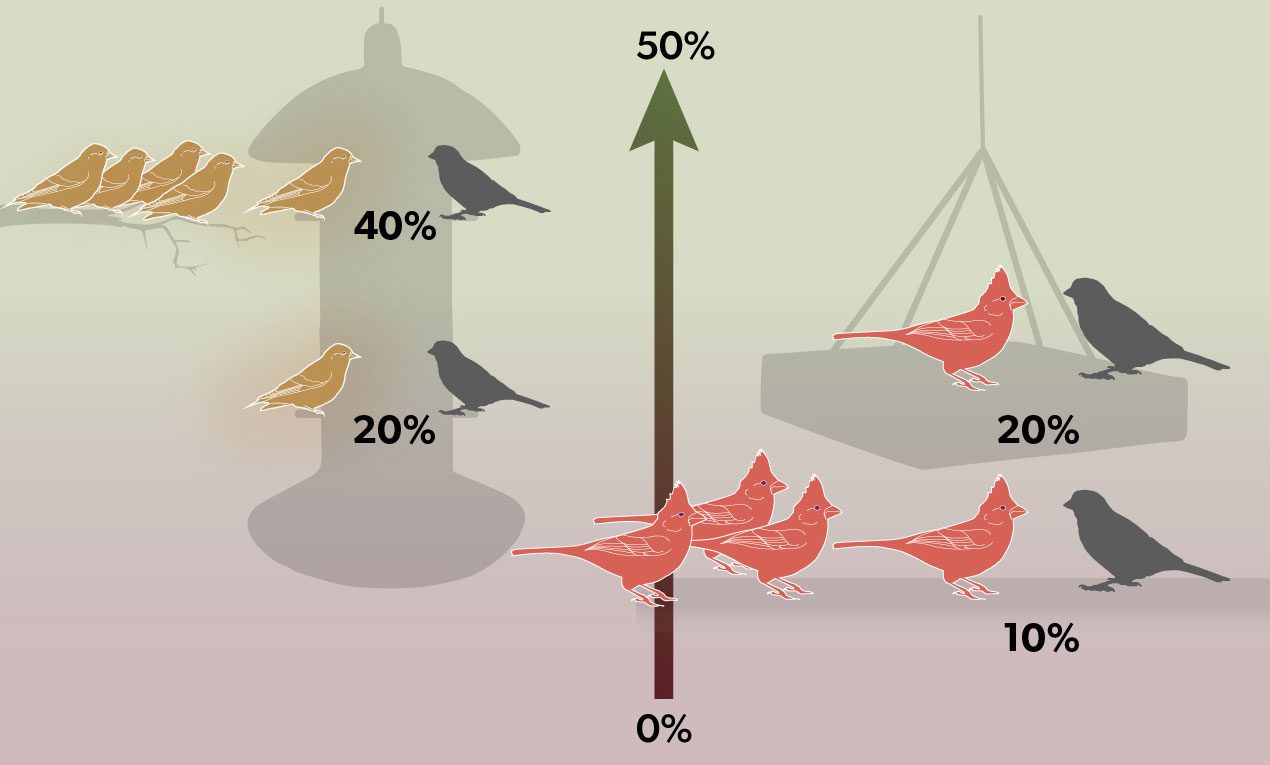

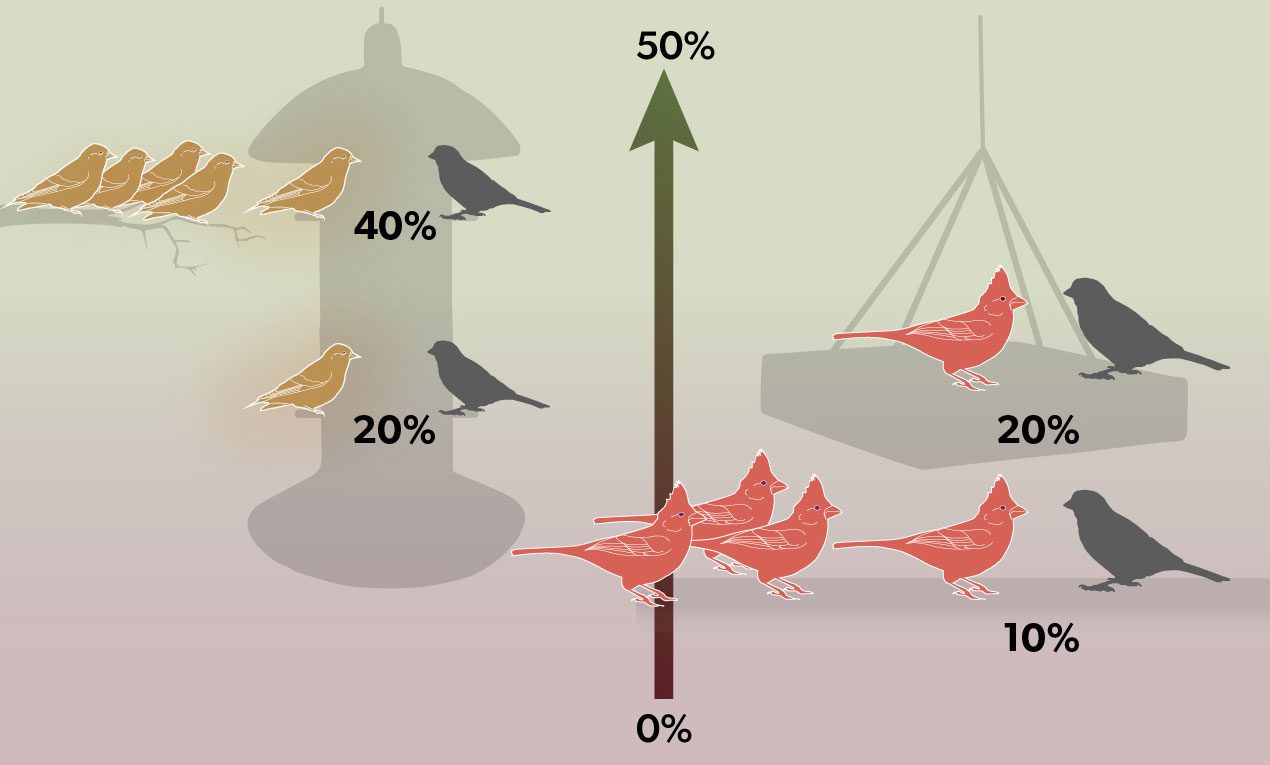

Subsequent the workforce seemed into 55,000 recorded one-on-one dominance interactions within the FeederWatch dataset to see if the loner birds or social birds are higher at displacing different birds. Their outcomes, printed within the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B in February 2023, confirmed that birds like White-breasted Nuthatch and Purple-bellied Woodpecker (lone wolves that had been among the many least social birds within the examine) had been additionally among the many more than likely to displace others. On the different finish of the spectrum, the social butterflies that normally visited feeders in teams, similar to American Goldfinches and Home Sparrows, had been more than likely to flee the scene when going through off in opposition to a foe of comparable stature.

However there was a caveat: When these socially inclined birds got here to feed in teams, their efficiency improved. For instance, extremely social Pine Siskins lose most encounters when they’re alone, however when a gaggle of 5 visits collectively their particular person interactions, on common, grow to be twice as profitable.

Conversely, some birds that are usually lone wolves, like Northern Cardinals, turned much less profitable in feeder showdowns after they visited in teams.

“We predict that these results could be pushed by what the birds are listening to,” says Dakin. “So possibly when cardinals are there in a gaggle, they’re paying consideration to one another and could be extra vulnerable to being displaced by a special species.”

One other examine, in press on the journal Nature Communications and led by Gavin Leighton, an assistant professor of biology at Buffalo State College, investigated what occurs to the dominance hierarchy when a brand new face reveals up on the chook feeder. Leighton and his workforce checked out round 1,600 interactions from greater than 100 totally different chook species within the FeederWatch information and decided that “syntopic” species—pairs of species that normally overlap in area and time—get into fights lower than anticipated. Then again, species that aren’t usually discovered collectively battle greater than anticipated when their paths cross.

For instance, chickadees, goldfinches, and juncos appear to keep away from stepping into scuffles despite the fact that they’re usually shoulder to shoulder at feeders. Then again, chickadees appear to be spoiling for a battle with Yellow-rumped Warblers.

“All of it comes all the way down to vitality,” says Leighton. “You don’t wish to get into fights you understand you’ll lose. When birds see one another regularly, they’re extra prone to know whether or not they’re the subordinate one or the dominant one. In case you are in shut proximity to somebody you understand is prone to beat you, it’s extra advantageous to simply depart earlier than something occurs.”

Each Dakin and Leighton are persevering with to make use of FeederWatch information to tease aside the social networks at chook feeders. Leighton is at the moment learning whether or not harsh climate makes it extra seemingly {that a} subordinate species will resist in an assault; Dakin is taken with how climate impacts group dimension at chook feeders.

Emma Greig, the venture chief for FeederWatch on the Cornell Lab, says she’s thrilled the information is being utilized in new methods, and that hundreds of FeederWatchers are persevering with to report dominance interactions of their observations.

“We are able to use chook counts to deduce issues about habits, however now we will additionally use folks’s direct observations of behavioral interactions to find out how birds relate to 1 one other,” says Greig. “It’s actually improbable information.”

[ad_2]